Bitters are a form of patent or proprietary medicine made by steeping herbs, roots, and other spices in alcohol. They likely originated from medieval apothecaries, and were first patented for sale in 18th-century England, where they were concocted by so-called physicians who claimed the bitters were remedies for digestive and circulatory disorders.

Bitters are a form of patent or proprietary medicine made by steeping herbs, roots, and other spices in alcohol. They likely originated from medieval apothecaries, and were first patented for sale in 18th-century England, where they were concocted by so-called physicians who claimed the bitters were remedies for digestive and circulatory disorders.

Of course, these cure-alls, which could be anywhere from 30 to 50 percent alcohol, were also a convenient excuse to drink. At times when indulging in booze was frowned on, an adult could take a regular swig from a bitters bottle “for good health.” Bitters reached their height of popularity in the United States between 1860-1906, around the time the Civil War was starting and the Temperance movement was gaining steam. Bitters also help drinkers dodge the “sin taxes” and other restrictions placed on alcohol first in England and then in the United States.

Because they live up to their name, triggering the “bitter” taste buds on one’s tongue, bitters were mixed with other spirits in the 18th century to make them more palatable. Thus, around 1806 in England, the cocktail was invented, a mix of bitters, spirits, water, and sugar. Some of the most common herbs and spices used in bitters are cascarilla, quassia, orange rind, gentian, angelica root, artichoke leaf, thistle, goldenseal, wormwood leaves, yarrow flowers, and quinine from cinchona bark. Bitters might be flavored by juniper, cinnamon, caraway, chamomile, or cloves.

In 1824, German-born physician Johann Gottlieb Benjamin Siegert, serving as the Surgeon General for Simón Bolívar in the fight for Venezuelan independence from Spain, formulated Angostura bitters—derived from the herb gentian and not angostura bark—as a remedy for

seasickness and other forms of nausea. He exported his product to England, where it was adapted by the Royal Navy in 1862. On navy ships, it would be added to gin to make “Pink Gin” cocktails, named for the color of the reddish tint the bitters gave the drink.

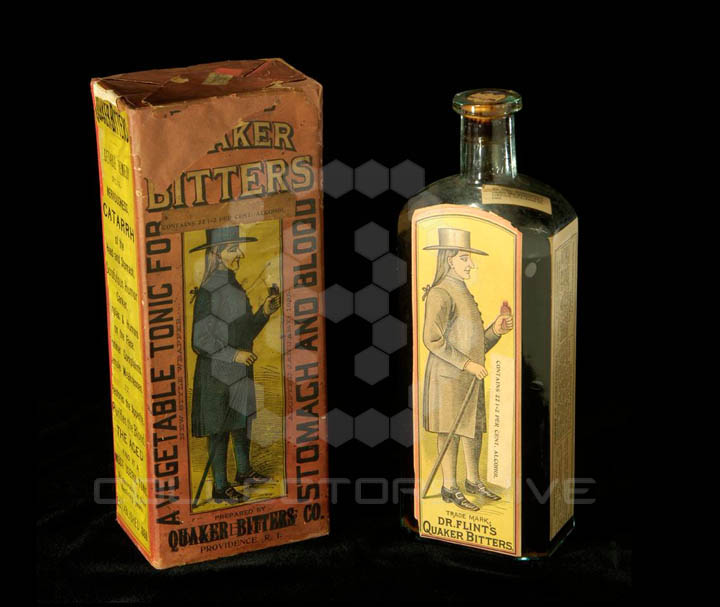

In 19th-century United States, bitters—as they were unhindered by the Revenue Act tax of 1862—tended to be pricey, and come in fancy, colorful figural glass bottles shaped like log cabins, Native American women, or fish. Once the contents were emptied, bitters bottles were often kept as decorative objects, instead of being tossed in the garage. For collectors, a bitters bottle must have the word “bitters” somewhere on the label or in the lettering to distinguish it from a regular medicine bottle. Bitters were also heavily advertised at this time, marketed on all sorts of giveaway items, including trade cards, clocks, signs, trays, tokens, stamps, decanters, and almanacs.

People believed that bitters worked, because the effects of the alcohol made them feel better, at least temporarily. While most makers tried to ascribe mystical healing properties to the herbs in their bitters, Greeley’s Bourbon Bitters were much more straightforward about the real “magic” of their elixir, boasting that it had “all the nourishing and invigorating properties of Old Bourbon Whisky.” Greeley’s came in a bottle shaped like an upright barrel with multiple rings at top and bottom. The most common colors found are copper, amber, puce, purple, and pink. Green is rare, while aqua and straw yellow are extraordinarily difficult to find.

Certain bitters bottles were shaped like human figures, mostly racial caricatures. One of the most collected is the Brown’s Celebrated Indian Herb Bitters bottle, patented in Philadelphia in 1868 by Neail N. Brown. The 12-inch bottle is shaped like a Native American woman with her hand resting on a shield, inscribed with the brand name. These were made in green, aqua, clear, puce, and both dark and light amber.

Another of these is the rarer Ta Tsing Bitters Bottle, patented by Meigs Jackson in 1868 in Clarksburg, West Virginia. The 11-inch-tall bottle for “The Great Chinese Remedy” is supposed to represent a Chinese man, wearing a cape with a long mustache and a long Manchu-style queue braid in the back. The front and back of the bottle, which has been found in dark amber and aqua, have indentations for the label and the lettering reads “R. S. Gardner & Co., proprietors, Clarksburg, W. Va.”

A much more respectful figural bitters bottle celebrated the United States centennial. Bernard Simon of Scranton, Pennsylvania, designed and patented a bottle in the shape of a bust of George Washington. Oddly, the opening of the 1876 Simon’s Centennial Bitters bottle was located on the bottom of the Washington bust, and it was closed with a cork that kept the liquor from leaking out when the president was right-side up.

Another popular bottle, which once held Dr. Fisch’s Bitters, came in the shape of—what else—a fish. Collectors have uncovered this bottle in various sizes and colors, but the smallest ones are likely reproductions. One example of an authentic “fish bitters” bottle comes in amber, and has the words “Dr. Fisch’s Bitters” curving part way around the eye. The reverse side has the letters, “H. Ware—Patented 1866.” Later version—generally 11 ½ inches tall and found in dark green, clear, golden amber, and dark amber—have “The Fish Bitters” arching around part of the eye and “W.H. Ware Patented 1866” on the back.

National Bitters, meanwhile, were identified by their 12 ½-inch “ear of corn” bottles, which came in several colors, with a husk and brand name on the front. This design was patented by Henry Schlichter and Henry A. Zug of Philadelphia in 1867, and it inspired several other corn-shaped bottles.

The Tippecanoe Bitters bottle had a more standard 9-inch bottle shape, but its texture was meant to indicate tree bark. The bottle, patented by Hulbert H. Warner in Rochester, N.Y., in 1883, is marked “TIPPECANOE” in one-inch letters on the front, and features a canoe on the back. Produced in Rochester, it came in clear, aqua, and amber.

The tremendously popular Drake’s Plantation Bitters bottle introduced the log-cabin motif when Mr. Drake patented the design in 1862. This 10-inch-tall four-sided cabin is simple, usually in the shade of amber and featuring no doors or windows. The bottle is usually embossed with, “S.T. Drake, 1860, Plantation, X, Bitters.” Several molds were made based on this patent. Earlier and more common bottles from the 1860s and 1870s have six logs above the label indentation, while bottles from the 1880s and later had just four logs above the label.

A year later, Charles Lediard of Brooklyn patented an 11-inch-tall triangular log-cabin bottle for O.K. Plantation Bitters, usually made in dark amber, with the lettering, “O.K. Plantation—1840.” Eventually, clever designers like George Scott in 1864 and John H. Garnhart in 1870 patented log-cabin or “cottage” bottles with windows and doors.

Particularly rare bitters bottles can command thousands of dollars at auction, while more common bottles sell for a few hundred. The most widely found, like Atwood’s Bitters and Lash’s Bitters, only sell for a few bucks a piece.

Other bitters bottles that are relatively easy to find are Drake’s Plantation Bitters in plain amber, Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, Dr. Baxter’s Mandrake Bitters, Doyle’s Hop Bitters, Electric Bitters, Dr. Flint’s Quaker Bitters, and Goff’s Herb Bitters. One of the reasons Hostetter’s is so common is that the diarrhea tonic, containing 47 percent alcohol, was purchased by the Union Army by the boxcar.

Bottles that are most coveted by collectors include Drake’s Plantation Bitters in unusual colors, Brown’s Celebrated Indian Herb Bitters, Dr. Fisch’s Bitters, Greeley’s Bourbon Whiskey Bitters, National Bitters, Simon’s Centennial Bitters, and Bourbon Whiskey Bitters, as well as Berkshire Bitters, Dingen’s Napoleon Cocktail Bitters, Harvey’s Prairie Bitters, Horse Shoe Bitters, Jackson’s Stonewall Bitters, Jacob’s Cabin Tonic Bitters, Kelly’s Old Cabin Bitters, McKeever’s Army Bitters, General Scott’s Artillery Bitters, Seaworth Bitters Company, Steinfeld’s French Cognac Bitters, Travellers Bitters, and Warner’s Safe Bitters.

The passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 delivered a near-fatal blow to the bitters industry. Any tonic or remedy containing alcohol or opiates was heavily regulated, which effectively ended the reign of patent medicine. Bitters were relegated to bars, where they have spent the past 100 years as mere cocktail flavorings (although aperitifs and digestifs like Fernet are currently growing in popularity as shots).

Collectors beware: Bitters bottles made by Wheaton Glassworks of New Jersey are all 20th-century reproductions, and are still made today.